my frontal lobe blinks on

by Jacob Ginsberg

We’re 50 feet above the Seekonk river, about halfway up the Crook Point Bascule Bridge, and for the first time in my life the rush of physical peril yields to crystalline foresight and a simple, forceful thought: I really don’t want to die.

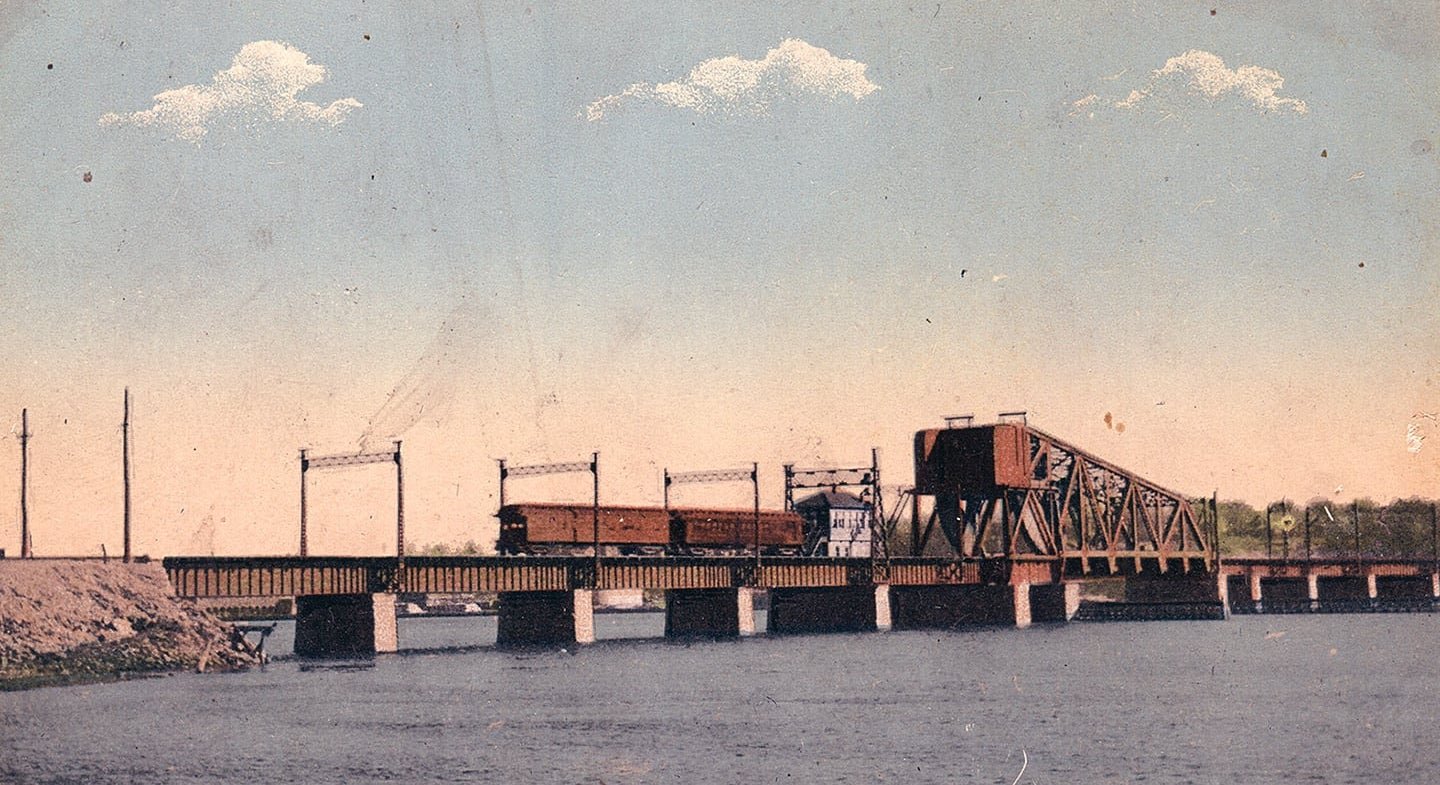

The bridge is an edifice of rotting wood and rusted steel. Long decommissioned, it’s permanently angled at 64 degrees, jutting across the river toward East Providence. It’s covered in graffiti. We passed “GOD IS DEAD” on consecutive trusses by the gate. Above us are cryptic tags and “MORE” in huge block letters. It’s a rite of passage for vandals, student athletes, and local punks. Apparently, there’s a swing chained to the top.

Hector studies urban planning, so he’s been going on about gentrification, about railway decline, about Rhode Island’s plan to demolish the bridge and the city’s plan to redevelop it. It was his idea to come here.

Austin studies philosophy and a little public policy. He’s been talking institutionalized racism and anarcho-syndicalism and maligning the toll of human enterprise on nature. He’s 15 feet above Hector, 30 or 40 above me.

I bounce between departments trying to figure out what to study — failed econ, failed calculus, barely passed neuro, haven’t pushed for an A in anything but English lit. Since I’ve been trying, lately, to not pretend like I know about something when I don’t, I’ve mostly been listening to the two of them. They know me as the type to climb shit, to teeter on the edge, to reach for one more branch in a tree for the thrill of dangerous height, which is probably why they invited me. I’ve seemed the ‘risk your death to feel alive’ kind of guy, until now.

Now, I haven’t spoken or moved in twenty minutes. I didn’t even look down.

Austin calls out to me. “Gins! It’s crazy up here! You can see the whole city.” He’s only a few feet from the top.

“Cool,” I say, hugging the steel. Its smell is undetectable in the marsh air.

He can’t hear me, and he’s starting to realize I’m maybe having a problem. “Don’t be afraid,” he says. “Come up!” On the walk over, he told us he believes in the mathematical universe and all possible realities. He equates dying with any other cessation of consciousness — he’s unafraid of blacking out, of fainting, of sleep, so why would he fear death? He keeps climbing.

Hector is lost in policy and visions for the future. He’s talking to the wind about reconnecting the people to the riverfront, about protecting the city’s history, about industry. He slips out a paint marker to write some message I can’t read. In doing so, he drops the cap, which falls and taps me on the head on its way to the water.

“I’m good here!” I yell. I think this one is audible.

And it’s true: I have thirty minutes of empirical evidence that if I keep still, I’m not going to fall. This is my home now.

The branching forward thinking I learned as a kid playing chess has come roaring back, but instead of piece exchanges I see action and consequence. I see a slip of the foot, a cramp in the palm, a crick of the neck as a cormorant swoops overhead, all the paths to watery demise. I see my parents at my funeral, my brothers in my empty bedroom. It’s kind of cool that I care about my life enough to be terrified of losing it, I guess. Cool that the existential smog might be clearing, but it’s hard to appreciate when I can so vividly imagine my death.

Hector is at the bottom now, taking photos, and Austin has reached the pinnacle and lowered himself to the swing. He glides up there, back and forth, more than 100 feet above the glass of the river, the sun beginning to set over Providence. He pumps his legs like a child at a playground, as if he can loop the swing around the bar if he leans hard enough.

All I can think of are the stupid things I’ve done unencumbered by prescience. When I was five, I ate a random mushroom I found in the woods. When I was twelve, I sledded into traffic. When I was fifteen, my brother and I aimed bows at each other and tried to catch the arrows. Two days ago, I tried to shotgun a beer while holding in smoke from a bong rip. Forty minutes ago, I climbed 50 feet up a defunct railway bridge on gated-off state property. I realize this is it. There’s no going back.

The sun has dipped away and night settles on the Seekonk. Austin’s made it down to Hector. They’re calling me, telling me I’ll be fine, to climb down. I am fine. I’m not stuck; I’m safe. Like I said, this is my home now. The night air is cool and my muscles are sore, but the bridge is steady, cradling me in the sky. I don’t look down at them or up to where I couldn’t climb but straight out, into the empty space above the river. A life could be had here, I know, but not a good one.

Slowly, I bend my knees and reach for a foothold beneath me.

Jacob Ginsberg (he/him) is a writer and teacher living in Philadelphia, PA. He's big into ospreys. His work has appeared in jmww, HAD, and other cool journals. He can be found on Twitter at @JacobGinsberg1.