MOOD; TRAGIC, DELIRIOUS

by Bill Whitten

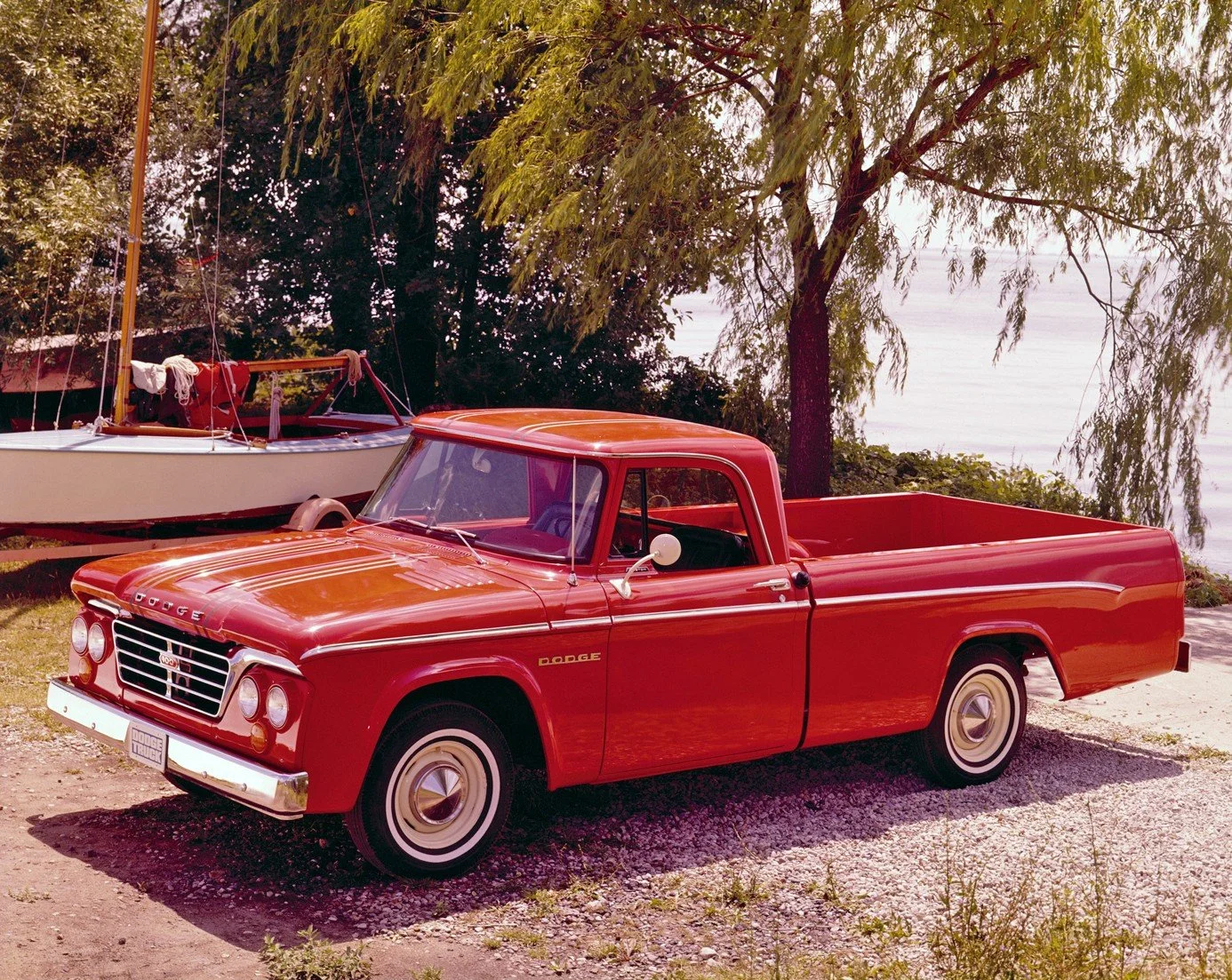

From the BQE, I steered my friend Bergamaschi’s beige 1987 Dodge D-100 pick-up to the exit that led to the Long Island Expressway. I was headed to Montauk.

Have it back by Tuesday was all Bergamaschi had said as he handed me the keys.

Stepping inside the truck one was greeted by the strange yet pleasant smells that old machines give off. There was an AM/FM radio, an inspection sticker from Idaho stuck to the windshield, a case of transmission fluid on the bench seat.

I liked to drive yet I knew I was a terrible driver. Behind the wheel, evidence of my liminal status as a member of society became obvious. I cut other drivers off, ran STOP signs, steered through red lights in a daze, was beeped at, screamed at by other drivers. Every time I adjusted the volume on the radio, I nearly swerved off the road. Surges of adrenalin and pangs of remorse were my constant companions.

Accompanying this awareness were the facts of my father’s and sister’s deaths in car crashes. Did their crashes raise or lower my odds of being killed in the same manner? Was my family genetically predisposed to violent death? Did I have any business getting behind the wheel of a car?

Ordinarily, I would take the train or the bus when I went anywhere, as my driver’s license had expired a decade earlier. However, the moment Bergamaschi made his offer, the idea of driving a borrowed pick up truck and traversing the highways like an outlaw became irresistible.

My hands gripped the plastic steering wheel. The last time I’d been on the LIE had been five years earlier as a passenger in a van ferrying a group of drunks and junkies to a rehab in Hampton Bays. The van had stunk of metabolized alcohol, body odor and stale cigarette smoke. The rehab, a former motel, had been filled with members of the NYPD, rock musicians and teenage junkies from Levittown.

I was there to escape a drug habit and a woman who claimed she was hopelessly in love with two men. She couldn’t choose between us. Tragedy, of one sort or another, seemed imminent.

It was all a lie, of course. You can only love one person at a time. In my absence, the woman moved out of my apartment into the other man’s, leaving behind most of her belongings.

Upon my return from the rehab, overwhelmed at the idea of living in a small space surrounded by her possessions, I immediately fled the apartment on Clinton Street, taking a panicky stroll that led me across town and eventually to the flower district. Near Sixth Avenue, I spotted a bundle of dried opium poppies hanging in the window of a flower wholesaler. I bought $10 worth of the poppies, returned to the apartment, pulverized them in a coffee grinder, made tea from them, all the while assuring myself it would be a harmless way to relax. Thus began a six-month binge.

Around the same time I received in my P.O. box a postcard from a certain Callie in Oklahoma City. On the front of the card was a photo of a largemouth bass, on its reverse were slanting, misshapen words of varying size and legibility. The postmaster had shown great skill in deciphering the address. From what I could make out, Callie’s brother had killed himself while one of my albums spun on his turntable.

On my couch, as I’d read and reread the postcard, I’d tried to introduce this new information into a belief system that held laziness as noble, dissolution as sublime and the squandering of talent as erotic, if not transcendent. Was it a black mark against my mortal soul that someone had killed themselves while listening to my music or was it the ultimate form of distinction?

In the intervening years, if I ever had reason to listen to that particular album or reflect upon its existence, I usually thought of the woman who left me and not about the man who committed suicide. She had been the inspiration for many of its songs. I still remember what I wrote in my journal the morning after I met her:

Her eyes were blue and shining, she wore a sleeveless ivory dress that looked cheap and poorly made. Sandals, one held together by duct tape, no stockings. She was nearly my height. Absent-mindedly she moved a plastic bracelet up and down her left forearm as we talked. That was the situation.

As I steered the truck onto I-495 West it began to snow. I dropped a lit cigarette on the floor of the car, cursed and crushed it with my boot heel. I reached into my coat pocket, fished out another and placed it between my lips. I checked the horizon, then the rearview mirror. The coast was clear; there were no police in sight.

Then I saw it.

To my left, a white tailed deer was trapped on the narrow median. Running in circles. Black eyes wide, alien. The grass slick with snow. Panicking, slipping nearly falling. Cars and trucks barreling by on either side.

Before I could even think to slow down, I was already past it. For a second I glimpsed the deer in the rearview mirror, running back and forth, back and forth.

The deer would inevitably become a metaphor, a symbol. I would tell someone about it, there was no doubt. I would tell them what it meant. The deer would be victimized once more by my need to ascribe meaning to a meaningless incident.

(Even trapped on the median the deer was more free than I.) I looked at my watch. I was late. Friends in Montauk, holed up in a rented beach house, were waiting for me. But I was always late to any event I was invited to or asked to participate in and come to think of it, so were my friends. Punctuality was incomprehensible to any of us. Arriving on time was the last thing I needed to worry about.

As I wondered what we would eat for dinner, the truck’s engine began to make a sound that could not be ignored or rationalized away. It was a death rattle. The steering wheel shook, the ‘check engine’ light flashed, the speedometer dipped. It occurred to me that Bergamaschi had known the truck would break down or even planned on it. I imagined him baring his brown teeth and laughing at the idea of my being stranded on the side of the highway in a snowstorm.

Bergamaschi, a writer, was still reeling, still bitter over the failure of his last novel. It was about a priest who used an ancient style of prayer to effect retrocausality, i.e. time travel. The priest prayed his way into a series of historical events. Bergamaschi’s description of these events was spare yet extravagant. He called it ‘maximalist minimalism’ and he’d considered the book and the style to be a breakthrough. After years of memoirs and autofictions he’d finally taken a risk. Yet, his gamble had led not to glory

but disaster. A complete fiasco. Sales were nonexistent and the reviews were uniformly bad. He was mocked, laughed at. He blamed his friends and his editor for letting him follow such a quixotic path.

Why hadn’t they told him that the premise, the idea was worthless? Why hadn’t they had the guts to call his manuscript ‘garbage’. It was because they were cowards and lackeys. He would never trust anyone again.

I’d liked the novel and considered it to be his finest. Take the long view, I’d told him. In twenty years, the book’s flaws will be looked upon as virtues.

He laughed at me. In twenty years no one will read books.

Bergamaschi’s truck drifted into the right lane. The noise increased and seemed to approach a crescendo, which surely would culminate with the engine bursting into flames. I pulled onto the shoulder and switched off the ignition.

Snowflakes landed on my eyelashes as I stepped away from the truck. Filaments of smoke leaked out from beneath its hood. The colors of the surrounding landscape – potato brown, spade grey, olive drab – were slowly disappearing beneath the snow. I walked with my back to the oncoming traffic, left arm and thumb extended

The highway curved as I moved over its continuous, infolding surface. With great precision, the world communicated the ominous menace of death, of history.

Naturally, I thought once more of my own history: my father calling me in New York at midnight one evening while he worked as a security guard in a paper mill on the banks of the Connecticut River. What do you think of the Herakleitos fragment B14, Bill? Have you ever really thought about it? Do you think it’s possible that Christ knew of Herakleitos? Maybe the question is: how could he have not known?

Whenever I traveled, the centrifugal force of memory strengthened to such a degree that it was as if my memories were in transit, not me. Up above, white clouds moved against a white sky.

Twenty yards away, a blue Volkswagen Jetta pulled to a stop on the shoulder. As I jogged toward it I thought of Bergamaschi looking out of his kitchen window at the snow, rubbing his hands together and picturing me frozen in a snowdrift.

I pulled open the door.

The driver of the Jetta would expect me to offer an incredible tale, which of course was the price of the ride. Whether it was true or false made no difference. It was the custom.

Bill Whitten is a musician and writer. He is the founding member of St. Johnny, Grand Mal and currently records under the nom de guerre William Carlos Whitten. His latest album Ecstatic Laments was released in June 2022 on Blue Car Records. His book BRUTES, a collection of short fiction was released in January 2022 on Too Big to Fail Press.