Rudy for rufus

by Doug Ross

I made a mistake. Again. Maybe he didn’t notice. He was the editor of an online magazine that I could see myself in. We’d both gone to a memorial event for my teacher—not his. He only hosted it. He only knew the man and his writing. I knew his teaching.

My teacher was usually desperate, run-around, unappreciated. All his agents and publishers dropped him after one or two books. The editor could see that and so he put him in the magazine. He ran my teacher’s last story. He published a series of three interviews and some of his line drawings. The third interview was his last. The final line drawing was his last. Of himself, at the desk.

I left the senate chamber early. I took the train to the bookstore where the memorial was being held. It occupied one corner of the store. That way people could keep shopping. I wondered if the editor had seen my name on the list. Almost everyone was a writer’s writer, like my teacher. The editor was a writer’s writer’s editor, and a poet. His first book of poetry had a picture of him on the cover and the second had a line drawing of his silhouette against a background, nothing else, besides the title. Maybe you were meant to think my teacher drew it. That would be a lie; illegal. For the last story, I thought, finding a seat, that would have made him my teacher’s editor.

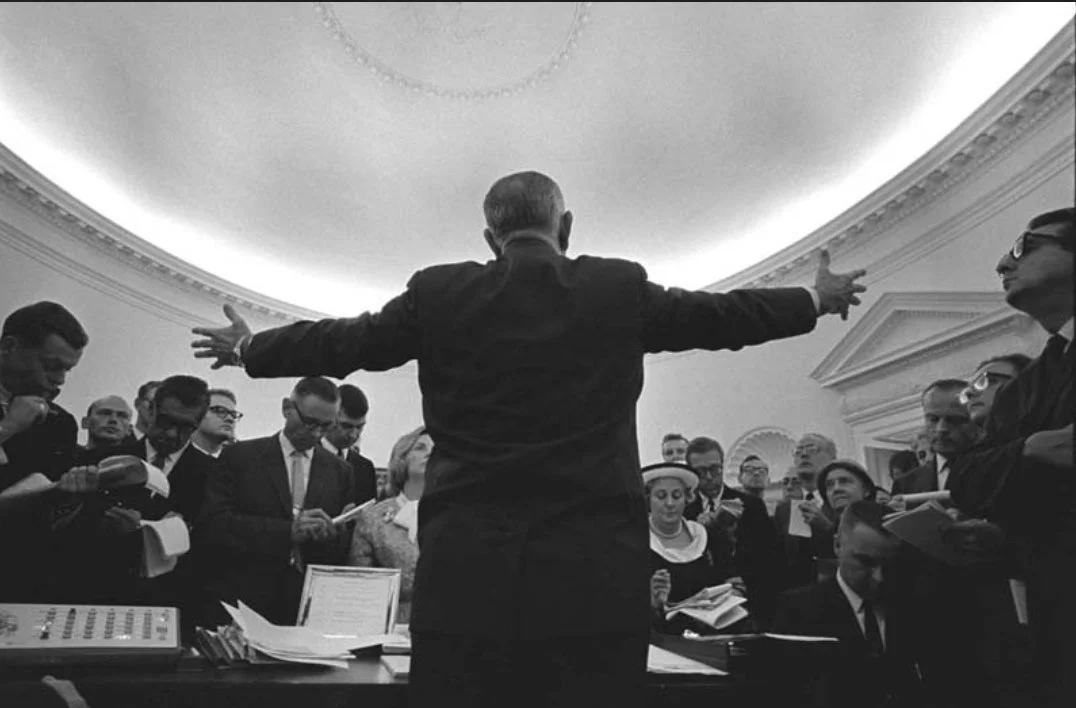

I really could see myself in his magazine. Not this story, but one of my good ones. Not one of the LBJs. He was spearheading a quiet movement over there, of writers devoted to my teacher. None had been taught by him. You couldn’t anymore. The best was a kid in his 20s from New Jersey, who’d reviewed some of his later books and was himself a literary agent. He did almost everything right by my teacher. The long paragraphs, plain language, honest, unpretentious, about writers, writing, winding around itself. To get his age I had to check his LinkedIn for the year he graduated. Then assume he was normal, that he hadn’t skipped any grades. He was never my teacher’s agent. I’m not sure if he was at the memorial. F. Murray Abraham came, though. Salieri. I couldn’t explain it. Salieri spoke very well of him.

I sat, thinking about how in my first submission I got the editor’s name wrong. I wrote “Jeremy” instead of “Jack.” I just used his father’s name, I told my wife, Lady Bird. They’re both online, I said. He will think I have been observing his father Jeremy, I said, online. But it turned out they had the same name. He was a Jack, Jr. I couldn’t bring myself to listen to the Last Interview. I should have mentioned—it was recorded. A couple months before my teacher died he let Jack Jr. into his home with equipment. It ran under the title: The Last Interview, once he knew that’s what it was. Along with a photo of my teacher with his arm on the editor’s shoulders. High but weakly.

To have been taught by him the editor would need to have gone to my school. It didn’t seem likely. The school was expensive. The editor had a little bit of working/middle class cache but not as much as other people in different quiet, though related, movements. His magazine was less drug, dead friend, fracture-oriented than some others. They respected my teacher even if they didn’t always follow him. They bent, let the language rupture a bit more than my teacher might have liked personally, or taught them to.

Their best writer spoke at the memorial. I had just paid him 750 dollars to read my novel. The second half–due on completion. I was safe; he didn’t know my face. I couldn’t pay the editor. Not even a dying man could pay him. I’d come to the memorial as a show of force. Let no one forget who my teacher taught. There were generations of us, thirty years’ worth. Only one could be the last. The generation that brought him out of retirement after his wife’s death. And then, a semester later, back into retirement. But we did not kill him, crucially, because he kept living. Would the editor remember that I had called him Jeremy, I wondered. Would death clear all accounts.

At one point this professor from my school spoke. She was in her 40s. She referred to him as a friend, a colleague, which I had no opinions on. He’d raised daughters; did I throw myself in the way of that? But they didn’t attend the memorial. This was for writers and editors and agents and an actor. The daughters had their own funeral and, most likely, sat shiva. My teacher had harmed them over and over again in his books. Shot, drowned, stolen, stillborn, burned. His wife, too. They were never truly dead. The fear of it made it humane.

After it came out I quote-tweeted the Last Interview. How many of his fucking masterpieces are out of print, I said. I didn’t speak during the Q&A. I sat in my chair and pretended to fall asleep, like I did at Georgetown dinner parties, when I was a congressman, and the topic had moved on from me. Sometimes I really was asleep. I’d come to the memorial alone. There was a ticket for Lady Bird but she said to just go. Be strong.

I opened my eyes. I thought I saw the New Jersey agent up front, talking to the editor. I couldn’t be sure, though I knew what he looked like. My teacher’s sentences take us from death to home, the agent wrote, in a review I’d found. If someone taught him that it wasn’t my teacher. I went home. I drank some Cutty Sarks. I had nothing but LBJs. I sent the editor the best story and then re-read it. I saw I’d made a mistake. The Kennedy people called him Rufus Cornpone when he was Vice President. Not Rudy. There was never any Rudy. Not even in Dallas. Another Rufus saved him–Youngblood. He put

his weight on Johnson. Crushed his head down in the limo. The Kennedy people mocked him. They were pretentious like that. They had all gone to Harvard. They all had a laugh at Uncle Cornpone.

My teacher had preferred Kennedy. As a young reporter, he chased him down on the steps of the Capitol, in killing range. He got the interview. Retreated to his desk. He learned there, to do it plainly, honestly, to get it done. He didn’t chase down Lyndon Johnson. There was no point. By Johnson, he was a writer.

Doug Ross is a writer and photographer based in Brooklyn. He grew up outside of Detroit. His stories have appeared in X-R-A-Y Lit, jmww, and New World Writing.