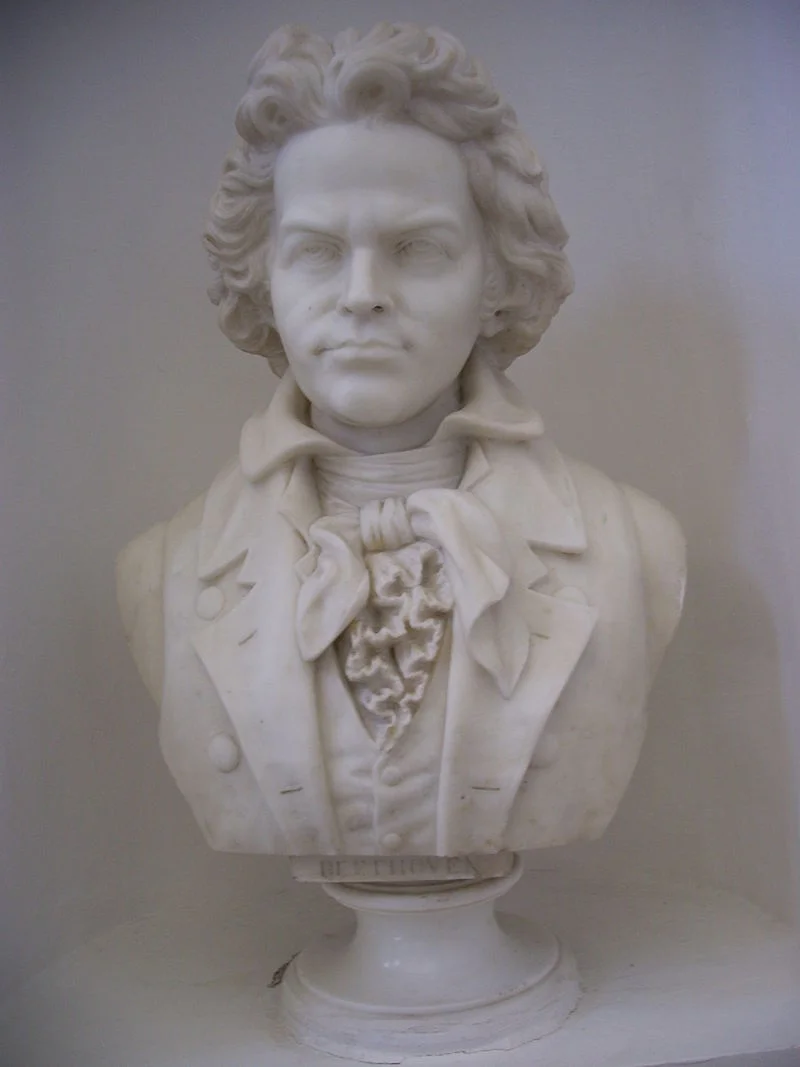

Beethoven

By Vanya Erickson

One afternoon, a delivery truck pulled up with a huge container for my father. I was terribly curious, but Dad shooed us out of the way until the thing had been uncrated and the deliveryman had left. I peeked from down the hallway.

Inside the cabinet, a hi-fi stereo with six dials and an automatic turntable gleamed—a 1962 state-of-the-art surprise for Mom. It was just like what I’d seen in TV commercials. Would I be allowed to play it?

Dad talked about that stereo all the way through dinner. “Just wait ’til you hear that beauty. It’s like having the orchestra right there in the living room!”

I’d never seen so much grinning on his face before. It altered everything.

As dinner came to a close, Dad announced his plan to listen to Beethoven that evening, and to demonstrate for us the power of the stereo—which garnered a groan from my brother, Don.

“Aw, Dad. Do I have to?” Don rolled his eyes.

Dad’s face fell, but I could see he wasn’t going to make Don stick around. That’s when I realized Don slithered out of nearly everything he didn’t like.

“C’mon Dad, it’s our sixth grade science fair tomorrow, and I’ve still got stuff to do. I don’t have time to waste listening to music by a guy who died a hundred years ago.” Don was already standing, feet turned toward the door.

I sucked in my breath at his disrespect. I would have dropped everything to be in the room with Dad’s grin, but Don didn’t seem to notice Dad’s happiness. He didn’t even have a science project, as far as I knew. He just wanted out, preferring to spend his time in his room with his dirty fingernails—reading mechanics magazines or taking apart old radios to see how they worked. Dad jerked his head toward the door and let him go.

My brother Walt sat across from me at the table, watching Don’s exit, his face like thunder, leg twitching to leave. Don had just beaten him at his own game, and there was no way Dad would let them both off the hook. Secretly, I was glad Walt was still at the table. He was fourteen, and always had some smarty-pants response to things that I wouldn’t dare say aloud. He was the one who gave KK and me our first cigarette, wrote lyrics that made no sense, and took time to play duets on the piano with KK even though there was an eight-year difference between them.

And now he was bursting to retreat to his room to listen to an album by a brand̵-new artist named Bob Dylan. Walt leaned toward me and said, “You gotta hear him, man, he’s like nothing you’ve ever heard before.” Walt’s passion made me smile, and I believed him.

“Bah!” Dad spat out. “What do rock ’n’ rollers know about music? Now, Mr. Beethoven—he was a real musician. You’ll see. You three meet me in the living room after you’ve cleaned up the kitchen.”

I looked over at the huge pile of dirty pots and plates. Walt would make some important excuse to retreat elsewhere for fifteen minutes, and so cleanup was left to KK and me. I thought of my book report that was due the next day—and I still had all those spelling words to memorize. I’d have to stay up late to finish everything. How long would this demonstration take?

* * *

KK, Walt, and I walked into the living room. Dad turned, and in a grand gesture swept one hand, palm up, toward the stereo. “Just look at this beauty. Your mother’s going to love it.” I knew she would. I could just imagine the soulful voices of Marian Anderson and Leontyne Price, warming the room like sunlight.

We gathered around, staring at the glistening knobs as Dad fiddled with this one, then that, but the best part was that automatic arm. I couldn’t believe my eyes when Dad pressed the lever. It floated over and landed softly onto the record, like magic.

“Are the speakers any good?” Walt asked, breaking the spell. “I mean, does the music lose quality if you crank it up?” Dad ignored him, and I plopped on the couch to wait for the music to begin.

“Get off that couch.” Dad’s words were suddenly raw. “You’ve got a job to do. The three of you spread out on the floor, in a semicircle shape like an orchestra, and face me.”

My eyebrows scrunched together. I wanted the happy dad back, but something had changed him. Was it my fault? I peeked over at Walt, who lifted a shoulder in response to my unasked question.

We sat on the floor exactly as he said. “Now. We all know you two are musicians,” Dad began, poking a finger in the air at little KK, and then at Walt. It was true. The two of them practiced on our great-grandmother’s big black piano for hours every day—not because they were told to, but because they liked to. How could I ever compete with prodigies?

But I was also a musician, wasn’t I? Why else would Mom ask me to sing with her around the grand piano in the evenings? Wasn’t I the one who always looked for a way to harmonize with a melody? It wasn’t the piano or a violin, but I could pick out the perfect harmony of a voice in my gut.

Dad’s voice boomed as his lecture continued. “Now, there’s a message just waiting to be discovered in every piece of music, but you can’t really understand the message, unless you pay close attention. It’s like a secret language that you need to decipher.” Walt rolled his eyes and looked over at me, shaking his head. Dad didn’t seem to notice.

“You all know Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, but what we’re going to hear is the one that came right before it, written in the summer of 1812 while our man Beethoven was trying to find a cure for his progressive hearing loss. You’d think that he’d give up, or that the music would at the very least be gloomy, but no! He was so confident about his work, he produced this gem.”

Walt whispered, “He may have been a genius, but he was also an arrogant asshole.” My eyes went wide at the forbidden word, but I liked the power it had. I whispered it under my breath to see what it felt like. My skin tingled.

Dad jerked his head at us. “Stop muttering. This is important. No matter what you do in life, you have to have confidence, and Beethoven had it in spades. Did you know that once, when he was accosted by a nasty critic after a performance, instead of boohooing about it, he responded, ‘What I shit is better than anything you could ever think up.’ Now that’s confidence for you. That’s Mr. Beethoven.”

Dad turned his back to us and lifted the top of the cabinet, as he slipped the record out of its sleeve and placed it on the turntable. “So tonight we’ll play the Eighth Symphony, and I will be the conductor. I’ll tell you when to come in, so keep a sharp eye out for me.”

“When to come in?” I asked.

“You heard me. You will play when I tell you to, and not a moment before. Listen and watch.” He closed his eyes and lifted a pencil, which appeared out of nowhere. Walt gawked at me as we both realized this was Dad’s baton.

The music burst from the speakers and we jumped. Dad’s arm shot out and he pointed down at Walt, whose smirk evaporated in the blast of sound. Walt stared wild-eyed as Dad’s head jerked to the pounding of the thunderous kettle drums, strands of his hair tossed into the air.

Then all at once the music slowed and filled with mystery, which drew me into Dad’s imagining, as I saw myself dancing alone on a stage like Clara in The Nutcracker, leaping and spinning late into Christmas Eve. Dad looked at me, eyebrows lifted as if he were telling a secret, and put one finger from his free hand to his lips as the music diminished.

I moved my imaginary bow slowly across my imaginary strings, as if I really could soften the sound. The violins vibrated from the speakers, building suspense, and Dad shook his free hand as if shaking off water.

Then the music darkened, as a heartbreak of chords told of tragedy, the sadness melting through my body. It was as if I was striding up a grassy hill, returning home after a long absence, and once there looked down at the valley below, my homeland, only to see devastation scarring the land. French horns brought to mind past battles and memories of loss. But embedded in the sound of the woodwinds and strings was defiance and resilience, as the music climbed to a tortuous intensity.

Beautiful and tragic. Slow and fast. Soft and loud. Each contrast twisted together into one. I thought of stolen visions I spied as I walked home from school: Dad’s stoic reflection in the garden, his hand reaching up into the branches of the trees to pick fruit. My thoughts moved to his sandpaper words, his cutting refusal to attend anything I was involved in. Somehow all of this was here in the music.

My father wasn’t this thing or that—he was all of it. The nurturer. The neglectful. The frightening. The brilliant. The longing for him to love me wove a pattern of exquisite beauty with the harmony of the music, and it was this that kept me rooted to the carpet at his feet.

Dad thrust out his arm, palm down, moving it slowly in a circular pattern as if stirring a huge pot of notes, swirling and blending them together. I was so mesmerized by his hand movement that when Dad next stabbed his baton in the air above me, it took me some time to respond. Did he know I was trying?

I soon discovered that Dad didn’t intend for me to be one single musician, playing one specific instrument. When he pointed, I had to play whatever came next, anything from oboe to kettle-drums. And when I responded to his cue, his eyes would close briefly and relax. His mind, just steps ahead, preparing for what was yet to come.

Dad’s eyes flew open moments later, wide and expectant, like a madman, reminding me of a photo I had recently seen of Einstein, hair sticking out at angles. In that instant I thought of my best friend Julie’s perfect father, with his grey suit and combed hair, cracking jokes and asking how Julie’s day was. Right now he’d be huddled over the kitchen table helping her with her homework. What was it like to have a father like that? Would her dad ever turn into Beethoven in the evening?

A Note About the Author: Vanya Erickson makes a living teaching writing and performing arts to schoolchildren in California. She currently studies with bestselling author Laura Davis as well as Brook Warner, former executive editor of Seal Press and cofounder of She Writes Press. Her work has appeared in OxMag and Gulf Stream Literary Magazine and is forthcoming in Evening Street Press.