pages of gold

by Edward Belfar

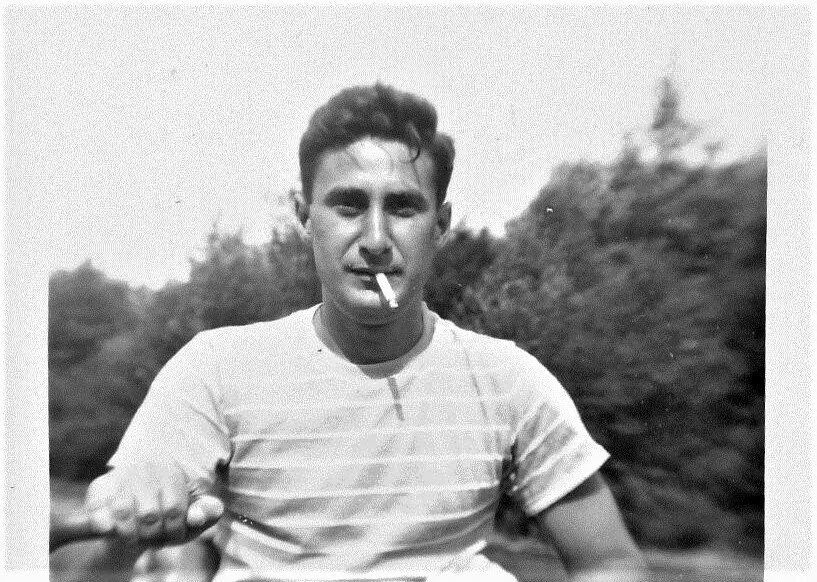

The photograph, black and white, three inches by five, slightly faded or a touch overexposed, captures my father rowing. With his lean upper body, his dark eyes staring directly at the camera, his wind-tousled, wavy black hair, and a cigarette dangling from his lips Bogart-style, he has a rakish, bad-boy look. The picture lacks a date stamp, and the background—some trees, a sliver of lake, an empty, white sky—reveals little about the location.

Still, I know who took the photograph and approximately when. The envelope in which I found it, just after my father died, also contained a letter, dated August 1942, from a woman I will call Ellen Wasserman. Eventually, I would find several more of her missives. The two maintained a correspondence—and more—for at least a couple of years, until late 1944.

The letters went to a Washington, DC, address, where my father lived for a time while grinding lenses for a defense contractor and waiting on his inevitable conscription. Ellen, originally from Holyoke, Massachusetts, was a nursing student in New York City, where the two had likely met before my father embarked upon his Washington sojourn. Owing to the geographical separation and, perhaps, though left unstated, the necessity for a young single woman of that era to guard her reputation, in-person meetings seem to have been infrequent. In November of 1942, however, in the most risqué line in all the correspondence, Ellen refers to a remark my father had made that her “kisses were delicious.” Her sly sense of humor reminds me of his own. A January 1943 letter starts, “Words written in diamond ink on pages of gold can hardly express my rapturous delight upon receiving your letter. (How’s that for a beginning?)”

Over time, however, her correspondence takes on a less whimsical tone. She complains of overwork and fatigue, asks repeatedly about when he will have vacation, voices frustration at his apparent evasiveness on the subject, and chides him for his often belated and terse replies to her letters. In July of 1943, she writes that she cries herself to sleep every night and muses about returning to Holyoke after finishing her studies. In December of 1944, she alludes to a misunderstanding stemming from a comment of hers in a previous letter concerning his draft status (apparently a sensitive topic for him, as his number would not come up until the last months of the war and he would never see combat). After first assuring him that she had meant no offense, did not doubt his courage, and hoped he would not have to go to war anyway, she lets her exasperation show: “Harry, it’s got to the point where I don’t know what to write for fear you’ll take it the wrong way.” Had we ever met, we could have commiserated. Though he would mellow some in his later years, my father would remain throughout his life a prickly sort, jealous of his dignity, quick to perceive a slight, intended or not.

That letter of December 1944 is, perhaps not surprisingly, the last of the bunch. Whether or not my father harbored any regrets about Ellen Wasserman I do not know. He never referred to her even obliquely in my or my siblings’ hearing, and we knew nothing of her existence during his lifetime. Why then did he keep the letters and that photograph taken on the lake from World War II to the end of his life, a period that included his fifty-two-year marriage to my mother? Perhaps the items held less meaning for him as reminders of Ellen specifically than of a time when, the shadow of the draft notwithstanding, all of life lay open before him, and by angling is cigarette just so, he could make a young woman—and perhaps even himself for a moment or two—believe that he was cut from the same rugged cloth as Sam Spade or Rick Blaine. Regardless, I consider myself fortunate to have found them. I also feel grateful to Ellen Wasserman for the wit, frankness, and acuity of perception that afforded me a glimpse into both her life and that of a young man named Harry Belfar, liberated at last from the narrow role to which I had always consigned him—that of my father. I hope that for her there did come a time of delights that only words written in diamond ink on pages of gold could have expressed.

Edward Belfar is the author of a collection of short stories called Wanderers, which was published by Stephen F. Austin State University Press in 2012. His fiction and essays have also appeared in numerous literary journals, including Shenandoah, The Baltimore Review, Potpourri, Confrontation, Natural Bridge, and Tampa Review.

He lives in Maryland with his wife and works as a writer and editor.