Candide: Make Sure You Know What You Want…

By Greg Coleman

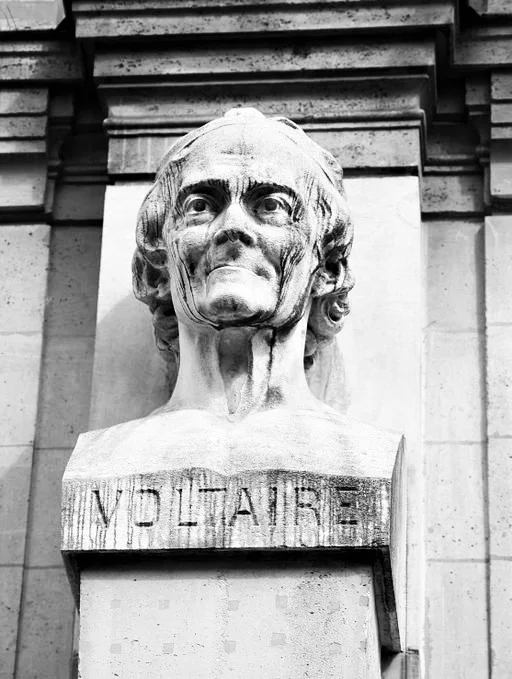

Having spent the better part of forty years teaching Voltaire’s Candide to talented students of French, I have learned that the conte, or short novel, contains the basic life lessons essential for every almost-adult to digest. Written in 1759, but startlingly contemporary in its relevance, the tale tells the story of the rather dim adolescent Candide who is (probably) the illegitimate son of the sister of the Baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh, one of the “most powerful lords of Westphalia.” The Baron is quite impressed with himself because he lives in a castle “with a door and some windows” and is married to the Baronne, who weighs about three hundred and fifty pounds. Candide lives in the castle with his aunt and uncle, their daughter, the 17-year-old Cunégonde, his alluring cousin with whom he falls hopelessly in love, and also with her brother, the future baron. Clearly, from the very beginning, we are in the realm of satire. Indeed, Voltaire was writing a satire of the German philosopher and mathematician Leibniz’s philosophy of optimism wherein the world we know is “the best of all possible worlds” largely, of course, because it is the only one we have.

The message of leaving home and discovering the sad truths of adulthood, the process of growing up which we all must face, is the lesson Voltaire uses to teach Candide and us.

This process begins soon after the beginning of the book when the Baron discovers Candide and Cunégonde hidden behind a screen getting to know each other all too well. The Baron is furious and kicks Candide out of the earthly paradise of the castle – a status which the impressionable and horny young man will try to regain, along with his beloved cousin, during the rest of the book. Voltaire plays consciously with the biblical references to the loss of innocence and the life in the garden after sinning, or attempting to sin. Leaving the protection and earthly delights of the castle literally throws Candide out into the world with no preparation and even less knowledge. For having tried to taste the “forbidden fruit,” he has been cast out, and worse than Adam, he is alone.

One other essential part of his life that Candide loses in leaving the castle is the tutelage of his teacher, Pangloss (“all tongue” in Greek) who sputters endlessly about optimism and teaches “metaphysico-theologo-cosmolo-stupidology.” Losing this particular influence may not have been so bad. In any case, Candide embarks upon a series of adventures which teach him the hard way that life has its adventures and its difficulties. The first of these is war. Candide, the immensely naïve young man, is “recruited” into a local war, imprisoned, and almost executed, only to be saved by the King of the Bulgarians (read: the Germans) at the last minute. In this altercation, combatants including Candide may at any moment be called a hero and/or thrown in prison and tortured. Absurdity reigns, and the best of all possible worlds has already been called into question.

Many readers have noted that the book can be compared to a movie, a travelogue, a satirical treatise, and to me most significantly, a quite modern-seeming cartoon. It is definitely a picaresque “novel of education” where a young boy-man travels the world and has an amazing number of experiences more quickly than seems possible in the “real” world. During these adventures, he is always looking for what he has lost, particularly his garden home and his cousin, and also a clue as to what it all might mean. This is complicated because his first and most revered teacher, Pangloss, is an idiot, and his lessons about the necessity of optimism run counter to almost everything that Candide sees and experiences from war to natural disasters and the Inquisition. Along the way, he does meet several others who serve as better teachers, particularly the Anabaptist Jacques, arguably the most admirable (and sympathetic) character in the novel; the pessimist Martin; a kind and resourceful old lady, and an ancient Turk whom he meets at the story’s end, in Constantinople. There Candide finally finds a version of his lost sanctuary in the farm where he and the other survivors try to work out the famously ambiguous message of the book: “We must cultivate our garden.”

The comic book-ness of the narrative is apparent in the lightning fast pace of the events whereby Candide travels around the world from Europe to South America and back, and the deaths and miraculous rebirths of several of the major characters including Cunégonde and Pangloss. What seems at first tragic becomes tragicomic and then, perhaps, ironically sad in that it is all there is and must be accepted. The future Baron, Cunégonde’s brother, is a case in point. After being supposedly slaughtered with the rest of the family in an attack on the castle, he is found again quite alive by Candide in Buenos Aires. Candide, who has become rich at this point, declares happily that now he will be able to find and marry Cunégonde at long last. The baron has a fit and basically responds, “Not with my sister you won’t,” at which point Candide realizes that the young baron is not worth it and kills him. Or he thinks he has killed him…he reappears again later as a slave down in the galleys of a boat, and is ransomed and saved by Candide. However, he remains unalterably opposed to his cousin’s marriage with Cunégonde. Candide, who has finally had enough, sends him back to the galleys. I think that Voltaire plays with the theme of death and rebirth here for comic effect as if this were Looney Tunes. The lesson is that one must make sure one knows who one’s friends and enemies really are, including family. And be sure a truly insufferable enemy is really dead or so far away that he can never return.

It would take a much longer commentary than this one to specify all the lessons which Candide—and we—can learn here. In addition to being wary about family as a source of security and support (particularly if you try to marry your cousin), it is fair to say that Voltaire distrusted most institutions, particularly the organized church. As he was a Diest, he believed in the existence of God but posited that God may have created the world but then left it and us to fend for ourselves. The standard comparison is to God as a watchmaker who made the clock but neglects to wind it at all. Accordingly, Candide finds himself in the Inquisition where he is beaten while Pangloss is hanged (not successfully, it turns out.) Jacques, an Anabaptist who believed in being saved by the confession of faith rather than by the church’s sacrament of infant baptism, is drowned without help from another man whom he had just saved. So, help others, but don’t expect that they will help you.

The center of the novel, a visit to El Dorado in what is now Peru, offers Candide another hope for finding the earthly paradise. He arrives there through the most arbitrary of plot maneuvers, but once there he encounters obligatory compassion, charity of every kind, a true welcome, and magnificent surroundings. In fact, there are gold “pebbles” everywhere which are considered as useless as pretty trinkets since everything is free. This seems to be, indeed, the country where all is well, but even this perfect place has it flaws. First of all, Cunégonde is not there, and secondly, freedom is limited. While one hugs rather than bows down to the king, one is not permitted to leave. Equality and fraternity—two thirds of the famous trilogy—reign, but true liberty is absent. Candide is granted special dispensation to leave with a large enough quantity of pebbles to make him, at least temporarily, a very rich man. He has also learned that good things are wonderful, but they may not last.

Toward the very end of the book, Candide flies almost literally to Constantinople for a reunion with most of his friends, and most importantly, with the delicious Cunégonde. Along the way, he meets a wise old Turk who suggests that in the real world life is not all fun and games and we have to work. He explains that work is necessary and keeps away three great evils: boredom, vice, and need. Work prevents us from getting in trouble through excessive lust and fooling around, a lesson that returns even though Candide learned it in the very first chapter of the novel. Work is also said to give us something to do, prevents us from being bored and, most practically, gives us the wherewithal to buy what we need to survive with some level of comfort. Martin, Candide’s pessimistic but realistic friend, adds that we must work without reasoning or philosophizing. In other words, that’s the way it is; we might as well accept it and get on with our lives. According to Martin, it’s the only way to make life endurable.

The brilliant final chapter of the book finds Candide, Cunégonde, Pangloss, Martin, the old lady, and others in their garden, the farm at Constantinople where everyone must work. The old Turk’s wisdom is in action: Candide is a farmer; the old lady takes care of the laundry; Pangloss continues to talk and teach, but now Candide no longer accepts what he says for revealed truth. Cunégonde “was very ugly, but she became an excellent pastry cook.” The beauty Candide sought for the entire novel is not so alluring or even nice any more, but she knows how to do practical work for the community. Their union is now more practical than passionate.

The book’s famous last line contains Candide’s response to Pangloss’ insistence that everything bad that happened was good and necessary in order for them to be in Constantinople. An optimistic point of view, for Pangloss, is the only option. Candide responds: “That is well said, …but we must cultivate our garden.” What cultivating the garden means, where it is, who are the “we” who must do it, and a thousand other aspects of this phrase have been the subject of numerous books, articles, and dissertations for over two hundred and fifty years. But the single word “but” seems to me the most important of all in that it reveals the fundamental truth that Candide has finally recognized: as he has begun to doubt what he hears, he has had to begin to think for himself. We have to grow up. We have to leave home and travel around to figure things out, and we cannot blindly accept what even very convinced and convincing elders tell us about “what it all means.” We have to figure it out for ourselves. We can listen to whatever THEY say, but this is our problem alone to solve.

A Note About the Author: Greg Coleman has an MA in French from Princeton and is a committed Francophile. He has lived in, visited, and led student tours to France many times in the last 45 years. For 32 years he served as a teacher and administrator at The Shipley School in Bryn Mawr, PA.